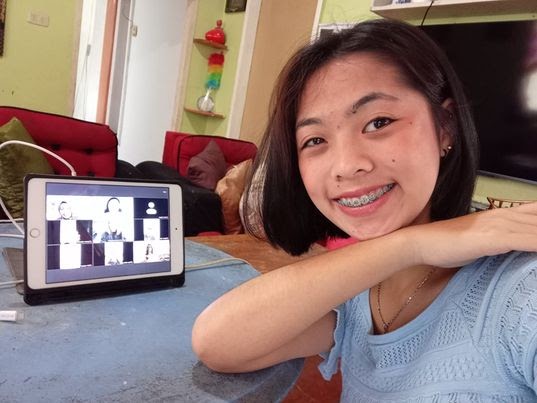

A student joins the deliberative forum on disinformation.

Abstract

The voices of ordinary Filipinos tend to be neglected in the body of initiatives towards addressing the challenges posed by disinformation in the 2022 elections. In an effort to address this, we conducted a three-day deliberative forum to ask a set of randomly selected Filipinos to generate recommendations on how to respond to election-related disinformation. We found that while many participants consider disinformation a serious problem in elections, this remains closely linked to the issue of money politics and the precarity of labour which leaves many digital workers at-risk of being recruited to serve as producers of disinformation. Participants also recognise the power of media in filtering information and shaping the narratives of the elections and wondered how this power can be made accountable to ordinary citizens. Lastly, they highlight the role of the individual in stopping the spread of ‘fake news’.

Key Findings

- For ordinary Filipinos, disinformation is part of the wider problem of money politics.

- They recognise that disinformation thrives because of precarious labour conditions.

- They consider preventing the spread of disinformation as the individual’s responsibility because they want to take control over their newsfeeds and make informed choices during elections.

Research Question

How do citizens characterise the problem of ‘fake news’ during elections?

Article Body

What does ‘fake news’ mean to ordinary Filipinos? How do they understand the impact of it in relation to elections? How can we address it? These are the questions we sought to answer when we conducted a three-day deliberative forum in April 2021. This is a continuation of the #DisinformationTracker project our team conducted from January to May 2019, which examined the disinformation tactics used by political campaigns in the Philippine midterm elections. This time, we aim to fill the gap in the body of initiatives to address disinformation. We find that one of the missing voices are those of ordinary Filipinos who are experts in their own right. Further, if provided the necessary tools, ordinary Filipinos are able to come up with concrete solutions to pressing issues such as ‘fake news’.

Twenty-five randomly selected Filipinos participated in a three-day online deliberative forum to discuss disinformation and elections from April 16 to 18. They represent diverse backgrounds in age, gender, location, and socioeconomic status. Together they learned from a fact-checker, a Facebook executive, an election watchdog, and disinformation scholars. After reflecting on these materials, they deliberated on the many issues surrounding disinformation and how we can best undertake it.

The first step was to set the ground rules. The participants agreed to use take turns in speaking, to keep calm, and to avoid using foul words.

Then deliberation started with the facilitators asking the participants to identify the issues related to ‘fake news’. They were divided into two breakout groups and returned to the plenary to share their groups’ discussions. Two major themes emerged from the deliberations: 1) ‘fake news’ is driven by money and it preys on the weak and 2) the individual is responsible for stopping the spread of ‘fake news’.

When the participants were asked to share key learnings from the expert testimonies, Ana, a 21-year-old former dental assistant, said she ‘didn’t realize politicians hired influencers to increase their impact on society.’ During the pre-deliberation interviews, many of the participants shared that vote buying is the top election-related issue they are concerned about. As Criz, a twenty-eight-year-old housewife from Bacolod puts it, ‘fake news is just like vote buying.’ ‘Politics and the media are interconnected,’ explained Boom, a twenty-one-year-old college student from La Libertad, Zamboanga del Norte. ‘Money is powerful,’ he adds, ‘it can make you a demon.’ Boom gave the example of a politician paying off journalists to spread stories that cast the politician in a good light to win votes.

Since those in power try to manipulate us, ‘We should be mindful of what we share,’ insists Gwapa, a businesswoman from Marawi City, ‘to protect those who don’t know better,’ she added. ‘Those who don’t know better’ consist of people who live in poverty. Because ‘if you really need [money,] you’re on the edge, you have no choice,’ says Lucky, a 32-year-old from Pangasinan. This observation connects to Jonathan Corpus Ong and Jason Cabañes’s research on the Architects of Networked Disinformation, where fake account operators see their role in perpetuating disinformation as nothing more than job that puts food on the table. Although the participants highlight the role of the individual in this ‘think before you click’ narrative, they also acknowledge the role of institutions in perpetuating ‘fake news’. They want to equip themselves with the tools to protect themselves against the collusion between politicians and perpetrators of disinformation.

After diagnosing the issue of ‘fake news’, the participants came up with recommendations to address it. They recommended the crafting of an anti-fake news and anti-trolling law but warned against the imbalanced implementation of the law in favour of the rich. The participants also endorsed the strengthening of the anti-dynasty law to prevent the concentration of power to a few families. After all, what is the point of having campaigns against disinformation if power remains concentrated on the hands of the few who can control information in other ways. Lastly, they advocate for the reinforcement of educational campaigns on disinformation targeted to people living in news deserts.

The deliberative forum is proof that when people with varying backgrounds and perspectives come together in a safe environment, we can come up with mutually-justifiable solutions to longstanding problems. Despite the polarizing nature of social media, these people from across regions in the Philippines with diverse views on politics, were able collaborate and generate collective wisdom.

We cannot dismiss citizens as passive consumers of disinformation. They too have become experts in disinformation based on their lived experience. They are eager to take part in policymaking when given the opportunity. In fact, the participants’ motivation for joining this project is their keenness to learn about ‘fake news’ and to give two cents on the issue. These reasons, among others, affirm the scholarship on deliberative democracy – that participants appreciate the intrinsic value of taking part in deliberations: to express their views and learn from each other. If people are given the chance to learn, deliberate, and listen despite their differences, public discourse can be a healthier place for democracy.

External link: From disinformation to democratic innovations: amplifying ordinary citizens’ voices